The author will use this page from time to time to present new ideas and to comment on recent archaeological discoveries which might have a bearing on the study of Romano-British place-names and river-names. The entries are arranged in chronological order, with the most recent one first.

[NB. Contributions given below are normally written on the assumption that the reader is already familiar with the contents of at least Chapters 1 and 2. Chapter 1 deals with the basic building-blocks of Celtic place-names and river-names. Chapter 2 explains how the basic building-blocks were assembled by the Celts to form compound names.]

Earlier entries:

19 October 2015: Petinesca, Carcasso, Camulosessa and like names - see below

28 September 2015: Manduesedo and like names - see below

09 September 2015: the Bindo..../Vindo.... names - see below

22 August 2015: Compound names of the Uxela, Iscalis, Loxa type - see below

10 February 2016

Flavian forts, the Trajanic frontier and Hadrian’s Wall

[Content transferred to Chapter 20: Rome's frontiers in northern England]

Petinesca, Carcasso, Camulosessa and like names

1 As explained in Chapter 4: place-names with an essa-type ending, Romano-British place-names with an essa-type ending have as the first part of the name, the part before the ending, either a land-name (a place-name made up of hill-letters) including the hill-letter s, or a river-name including the corresponding river-letter b, which may be changed to v. Those in which the first part of the place-name is a land-name are Begsesse, Yposcessa, Camulosessa, Certisonassa, Demerosesa and Raxtomessa, and those in which the first part is a river-name are Abisson, Devionisso, Duabsissis and Tuessis.

Brief notes on some of the above names will help the reader understand how the essa-type ending was used.

Camulosessa As explained in Chapter 15: Roman place-names in the north of England, this appears to have been the name of an early fort built at the top of a steep escarpment on the north bank of the river Derwent at Malton in Yorkshire (not to be confused with the later fort built a little to the north in Orchard Fields).

Duabsissis and Certisonassa As explained in Chapter 4: place-names with an essa-type ending, these appear to have been the names of forts at Berwick-on-Tweed (one name used in the Flavian period, the other in the Antonine period). Iron Age Duabsissis/Certisonassa was (were) probably at the top of the steep slopes on the Berwick side of the river, whereas Roman Duabsissis/Certisonassa is likely to have been a fort/harbour at Tweedmouth.

Abisson Again as explained in Chapter 15, Abisson appears to have been an early Roman fort at Durham, the name having been transferred to the Roman fort from the Celtic promontory fort now called Maiden Castle. The drop down to the river from the promontory fort is steep.

Tuessis This appears to have been the name of the Roman fort now called Bertha, at the confluence of the rivers Tay and Almond to the north of Perth. The ground at this point is not very high above the rivers but is bounded by steep embankments on its southern and eastern sides. Nonetheless, the name is likely to have been transferred to Bertha from the Iron Age hillfort on Dow Hill (NGR: NO 149 215), adjacent the Tay downstream from Bertha.

Demerosesa This appears to have been the name of the Roman fort at Drumquhassle, built up on high ground near the town of Drymen, near the southeastern corner of Loch Lomond, Scotland, there being a steep drop down to the Endrick Water.

All of the places with the names indicated above appear to have been built at the top of a steep slope at a point overlooking a river.

2 There were of course names with an essa-type ending on the Continent, too. A number of these are indicated below. Note that a name is not listed below if scholars in the country concerned are not in agreement as to its identification, as for example Catorissium in the French Alps.

The Continental names which appear to have an essa-type ending include:

Ambrussum at Villetelle, a little southwest of Nimes in the south of France

Carcasso at Carcassone in the south of France

Carissa Aurelia just north of the eastern end of the Embalse de Bornos, which itself is to the northeast of Cadiz in southwestern Spain

Cossa at Lamothe-Capdeville, just north of Montauban in the south of France

Cossium at Bazas, southeast of Bordeaux

Durocassium at Dreux, to the west of Paris

Iessos at Guissona, northeast of Lleida in northern Spain

Lebrissa at Lebrija in the Seville province of Spain

Ruessio at Saint-Paulien, southwest of Saint-Etienne in central France

Suessionum at Soissons, northeast of Paris

Turiasso at Tarazona in the Aragona province of Spain

Vindonissa at Windisch in Switzerland

Again notes on some of the above names will help the reader understand how the essa-type ending was used.

Carissa Aurelia Roman city on top of a steep-sided hill.

Cossa Gallic fortified site on a hill close to the river Aveyron. The hill goes up to about 100 metres above the river, with a steep drop down to the valley.

Durocassium The name, assuming it is complete, comprises the element duroc meaning ‘summit of hill steep’ (compare the final part of Vresmedenaci, the original spelling of the name of the fort at Ribchester in Lancashire) and an essa -type ending. The original Durocassium was thus at the top of a steep hill. However, the river Eure and its tributaries the Blaise and the Avre cut through a plateau in this region and so there are steep slopes almost everywhere along those three valleys. The name is thus of no great help in localizing the original settlement. However, the river-letters corresponding to the hill-letters r and s in Durocassium are s and b, both of which are present in the river-name Blaise, so it is probable that the original settlement was more or less on the site of the later, Roman fortress, believed to have been in the vicinity of the Chapelle Royale Saint Louis, overlooking the river Blaise.

Ruessio It is not absolutely clear that this is a name with an essa-type ending. The form given in the Peutinger Table is Revessione and in Ravenna Ribison. The Ravenna form is probably the earlier and is a straightforward topographical compound in the hill-letters r and s, where the old-style element bis means ‘high hill’. The name refers to an oppidum of the Vellavi, built on a steep-sided plateau overlooking the rivers Borne and Gazeille and about 66 metres above the rivers. The plateau extends into a north-stretching loop of the Borne and the Gazeille flows up the western side of the plateau to join the Borne.

Suessionum A Gallo-Roman city located only some 3 metres above the river Aisne. The name is generally taken to be derived from the tribal name Suessions, but the relationship is likely to be the other way round. The Suessions will have been the people of Suessionum, where the latter is a topographical description, not of Roman Soissons, but of the earlier, Celtic settlement just upriver at Villeneuve-St. Germain. At this point there is a hill adjacent the river, the hill rising to about 40 metres above the river. Even at a point very close to the river the ground is still some 15 metres above the river, so the drop down to the river must be quite steep. The Romans will simply have transferred the name to the new city which they built on the site of modern Soissons.

Turiasso Roman city adjacent the river Queiles. There is high ground immediately west of the modern town, this rising to some 85 metres above the river. The drop down to the river is steep. Perhaps the original settlement was up on the high ground.

Vindonissa This Roman fortress stood on a plateau some 30 metres above the confluence of the rivers Aare and Reuss to the NW of Zurich, there being a steep drop down to the Reuss.

Again one can see, even leaving Ruessio and Turiasso on one side, that these names refer to places built at the top of a steep slope.

One can see here a striking difference with the Romano-British names with an essa-type ending – with the possible exception of Suessionum at Soissons these names do not include the hill-letter s in the first part of the name. However, this uniqueness of Suessionum may suggest that the first s in Suessionum is not in fact the hill-letter s but the river-letter s and that the initial Su was really Sv and had earlier been Sav (cf. Ruessio and Revessione referred to above, and Tuessis and Tavessis, where Tav was the Celtic proper name of the river Tay in Scotland). The initial Sav may then have changed to San, which has come down to us as the river-name Aisne (the river at Soissons).

3 It is worth considering here a further group of names – those with an esca-type ending. These names are:

Caranusca in the Thionville area of northeastern France (Hettange-Grande?)

Castrum Prisco somewhere near Cordoba in southern Spain

Lavisco in the French Alps (Les Echelles?)

Matisco at Macon, to the north of Lyon

Namascae at Annemasse just to the southeast of Geneva

Osca (earlier Bolskan) at Huesca in northern Spain

Petinesca at Studen on the river Aare in northern Switzerland

Tarasco at Tarcason on the river Rhone in southern France

Verovesca (or Virobesca) at Briviescas, near Burgos in northern Spain

Vindisca at Venasque, southeast of Carpentras in southern France

Vipasca at Aljustrel in southern Portugal.

Again it is useful to give brief notes on some of these names, so that the reader can see how the esca-type ending was used.

Matisco The Roman fort was built on the site of a Celtic oppidum on top of a rocky outcrop extending from the high ground to the west of Macon to a point very close to the river Saône. The oppidum, and later the Roman fort, was protected by rocky escarpments on its N, E and S sides but connected at its western side to the high ground to the west. At its highest point the site is some 9 or 10 metres above the river Saône.

Namascae The name was probably originally that of a pre-Roman settlement on the mountain called Salève, which is to the south of Annemasse and rises to a height of some 400 metres above the modern town (at the part of the mountain nearest to Annemasse). The name will then have been transferred to a new settlement down on the low ground where Annemasse now stands. However, there is another piece of raised ground, Haut Montoux, immediately southeast of the modern town and that rises to about 40 metres above the town – that hill-top looks more suitable than the Salève mountain for a fortified site. Note that the hill-letters m and s of Namascae correspond to the river-letters r and b, changed to v, in Arve, the river at Annemasse.

Osca Said to be a simplification of the earlier Iberian name Bolskan. The Iberian oppidum and later Roman city were built on raised ground bounded on its eastern side by a steep slope facing the river Isuela.

Petinesca A Roman post at Studen, close to the river Aare in northwest Switzerland. The name will originally have been that of the Celtic oppidum built on top of the steep-sided hill which rises immediately west of Studen. The P will have been a B originally and the t a d. There is a hill-letter missing between the B and d, the first part of the name then being an old-style element of the Bindo-type meaning ‘high hill summit’ (though perhaps with a different hill-letter), which is entirely appropriate for the location.

Vindisca A fortified site on top of a lofty, steep-sided promontory towering above the valley of the river Nesque.

4 It is thus clear that the essa- and esca-endings were in fact used in the same manner, so it seems quite clear what happened. The esca, isco, asco, osco, usco element (the vowels are not important) was a straightforward inversion-type topographical element in the hill-letter s. It meant ‘hill steep’ and the people who used the hill-letter s normally placed this element at the end of a name, quite regardless of whether the name was an old-style or an inversion-type name (just as other people placed the duno-type element at the end of a name). The hill-letter s does not therefore appear at an earlier point in the name. The names with this element occur mainly in southeastern France and in the Iberian peninsula. Then at some point the c of these elements changed to s, but the element - now of essa- form - was still regarded as a topographical element including the hill-letter s, so this hill-letter does not appear earlier in the name. The names of this kind are found mainly in southwestern France and in the Iberian peninsula. Then, at a still later date, the essa-type ending ceased to be regarded as an element in the hill-letter s – it was regarded just as a name-ending applied to names of places which were at the top of a steep hill. But because it was no longer regarded as an element in the hill-letter s the people who used the ending did indeed insert their hill-letter s in the name of the place - this is the standard pattern in Britain, and may also be true of Suessionum at Soissons in northern France.

5 A few names call for special discussion.

Evidensca As explained in Chapter 16: Roman place-names in Scotland, this name was probably Levidanum before the arrival of the Romans and the latter simply added isca in order to distinguish this Levidanum (at Inveresk) more clearly from the Leviodanum at Doune. This may be an indication that the fort at Inveresk was built or garrisoned by a vexillation of the Legio II Augusta. This legion had earlier been stationed at Isca at Exeter and they seem simply to have transferred the name of their old base to their later fortress at Caerleon. The same may have happened in the case of the Inveresk fort and then Levidanisca lost its initial L and became the Evidensca of Ravenna.

Olerisca This appears to have been the original form of Ravenna’s Olerica at Maryport in Cumbria. This location is so very far north of the other names with an esca-type ending that it is probably wiser to look for a different explanation of Olerisca. This name may in fact have begun as Isca, just like the Isca at Exeter. The hill-letters r and l will then have been added in an inversion-type manner by later settlers. In some of the examples on the Continent, however, the esca-type ending has plainly been added on to the end of an old-style element, as in Caranusca, Castrum Prisco, Petinesca, Vindisca and possibly Vipasca (probably something like Brivasca or Binvasca originally), whereas in other examples it has been added to the end of an inversion-type element, as in Lavisco (possibly Lacisco originally), Matisco (though probably Madisco originally, where mad is an old-style element meaning ‘hill summit’) and Tarasco (probably Darasco originally, where dar is an inversion-type element meaning ‘summit of hill’).

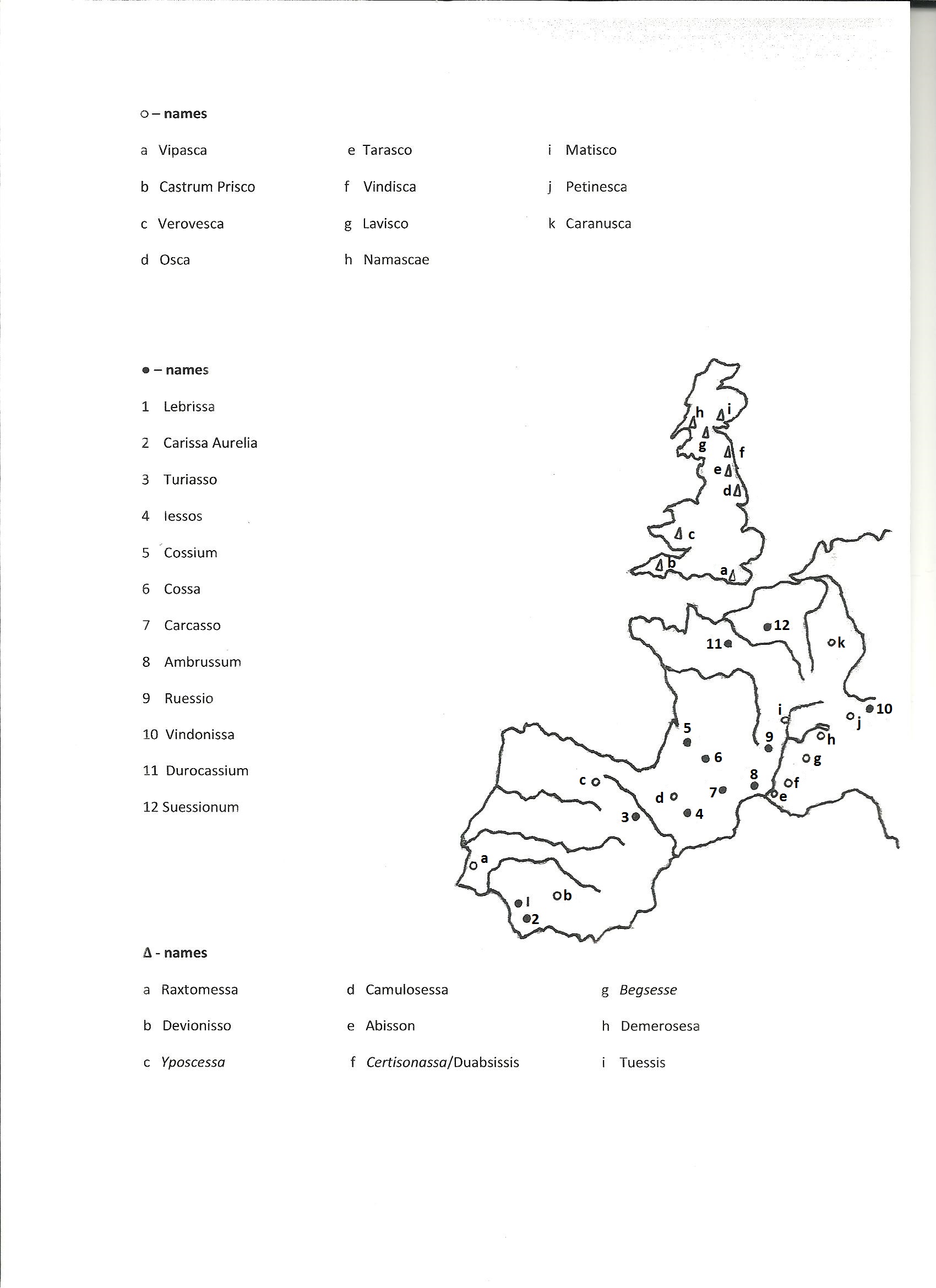

6 The map below shows the distribution of names with an esca-type or essa-type ending in western Europe.

○ – names with an esca-type ending

- – names with an essa-type ending and no hill-letter s in the first part of the name

∆ - names with an essa-type ending and a hill-letter s in the first part of the name

(The third group includes those names in Britain which have a river-name before the essa-ending).

Note that Catorissium (somewhere in the French Alps, with many scholars favouring a location at or near Bourg d’Oisans) may not be a name with an essa-type ending. Catorissium is the form given in the Peutinger Table, whereas Ravenna gives Cantourisa. The Ravenna form is likely to be the earlier of the two (the Cosmography is believed to have been produced around AD700 but the compiler appears to have used 1st century maps, at least for most of the names in Britain – perhaps the same was true for many regions of the Continent), and cant is the well-known transitional element meaning ‘steep hill high’ – the element is found, with slightly varying spelling, in Cunetio, Gabrocentio, Concanata (the Congavata of the Notitia Dignitatum) and Durcinate. The Peutinger Table form has dropped the hill-letter n and has changed ourisa to orissium, but the r and s of the Ravenna form might just be the hill-letters r and s.

It is clear from the above map that names with an essa-type ending and a hill-letter s in the first part of the name are found only in Britain (and possibly at Soissons in northern France). Secondly, it is clear that in France names with an esca-type ending are found only on and to the east of an axis formed by the course of the Rhone and Saône rivers, and that names with an essa-type ending and no hill-letter s in the first part of the name are found only to the west of that axis.

7 As noted above, there is a concentration of names with an esca-type ending on and east of the Rhone-Saône rivers. But it is clear that the people who used that element merely added it to the end of already existing place-names, so they had come to that region from somewhere else. But from where? They appear not to have come over the Alps from northern Italy since, so far as the writer is aware, there were no names with an esca-type ending in that region. It is traditionally believed that the Celts migrated from western Europe to southeastern Europe and later crossed over to Anatolia to form the kingdom of Galatia. But one wonders whether there might at some time have been a migration in the other direction, perhaps a migration by sea from southeast Europe to the region of southern France east of the Rhone. Later, the descendants of those migrants may have crossed the Rhone and taken over various settlements in southwest France, their place-name ending esca by now having the form essa. And later still, further descendants may have moved north and then crossed to Britain, by this time the essa-type ending no longer being regarded as an element in the hill-letter s, so that these people added both the hill-letter s and the essa-type ending to already existing place-names.

Manduesedo and like names

1 The name Manduesedo is thought by scholars to be based on a hypothetical root mandu considered to mean ‘small horse’ or ‘pony’, and another hypothetical root essedo taken to mean ‘war-chariot’ or ‘cart’. Manduesedo will have been the name of the Roman fort and fortress at Mancetter, built on high ground on the western side of the river Anker, the name simply having been transferred by the Romans to the civilian settlement on the other side of the river, on Watling Street. It is of course impossible to prove or disprove that the location of the fort Manduesedo had anything to do with small horses or ponies, but if it can be shown that all places with names of the mandu-type did in fact have a certain topographical feature in common, then it is logical to conclude that mandu is a topographical element and has no connection whatsoever with small horses and ponies.

1.1 Cramond, the Roman fort in the western outskirts of Edinburgh, includes the element mond, which one might think could be a back formation from the river Almond. But if we assume mond to be a topographical compound in the hill-letters m and n then the corresponding river-letters are r and m (for main rivers) and both of these river-letters are in fact present in the river-name Rumabo, this name having been transferred from the river concerned (now the Almond) to a Flavian fort built close to the river, most probably at Cramond itself, though no trace of that fort has yet been found. The place with a name including the element mond is, however, much more likely to have been the hillfort on Craigie hill, on the north side of the river Almond at a point just north of Edinburgh airport. At some point the hillfort was taken over by people who used the hill-letter l, most probably l2, and the name became Lamond or Almond. The Flavian fort was abandoned a few years after AD86 and when the Romans later built their Antonine fort at Cramond they simply transferred the name and presumably the inhabitants of the hillfort to Cramond. And then at some later date the Romans simply transferred the name Lamond/Almond to the river, which is why the river now actually has a land-name (a name comprising one or more hill-letters). But the important point to note for present purposes is that Mond was the topographical name of a place up on top of a hill. And the same can be said of Manduesedo, for although the Roman fort at Mancetter was built on raised ground it is much more likely that Manduesedo, or just the Anduesedo part of the name, was originally the name of the Oldbury hillfort built on top of the hill immediately west of the Roman fort. It is possible that the hillfort was called Manduesedo and that the Romans simply transferred the name to their new fort built on raised ground at the foot of the hill, but equally possible that the hillfort was just called Anduesedo and that a people who used the hill-letter m built a new settlement down at the foot of the hill to replace the hillfort, that new settlement then being called Manduesedo. The Romans then simply applied this name to their fort.

1.2 No other Romano-British name with the element mand/mond comes to mind, unless Ravenna’s Mantio at Manchester was originally Mandio – the fort was built on a bluff.

1.3 There are, however, two Continental names which repay consideration.

1.3.1 The element mandu appears in Epamanduodurum which was at Mandeure on the river Doubs in eastern France. It is not clear why this place should be thought to have had a special relationship with horses or ponies. Mandeure lies at the bottom right-hand end of a north-stretching loop of the Doubs. A little down the left-hand side of the loop lay what is thought to have been an industrial suburb, at the place now called Mathay. Between Mandeure and Mathay, and extending into the river-loop, is an area of high ground rising to about 150 metres above the river. But there is also high ground on the other side of the Doubs, opposite Mandeure, this rising to about 100 metres above the river. Now, on the assumption that the name Epamanduodurum was created in the same manner as place-names in Britain, the p at the beginning of the name is probably a modified b, this being the adjectival b meaning ‘high’ and qualifying the hill-letter m. The and is an old-style element meaning ‘hill-summit’, this element being qualified by the previous name of the hill, namely Ebam meaning ‘high hill’. And the durum element is just a dunum-type element but using the hill-letter r (compare the final element of Lutudaron at Wall in England) - it means 'summit of hill' or, more generally, 'on the top of raised ground'. It thus appears that Epamanduodurum is a straightforward topographical name referring to a site up on the high ground to the north or south of the river Doubs at Mandeure. A fortified site in either location would give its occupants complete control over all movement along the valley of the Doubs, the valley being fairly narrow at this point. The later Roman town was built on the low ground on the south bank of the Doubs, though its theatre was built into the hillside, as in so many other places.

1.3.2 The second name is Viromandis at Vermand, a little to the west of Saint-Quentin in northern France. Vermand stands on a terrace about 33 metres above a stream called L’Omignon. The terrace forms a peninsula of high ground jutting out into lower ground from an area of high ground to the north, there being a neck of high ground linking the terrace, on its northern side, to the area of high ground. Again, as in the case of Epamanduodurum, there seems no particular reason why Gallo-Roman Vermand should have more to do with horses or ponies than anywhere else. But the name Viromandis, with the initial V changed to B, is a precise and correct topographical description of the location. The initial Bir of Biromandis is an old-style element meaning ‘high hill’, the m is just the hill-letter m, and the nd means ‘hill-summit’. To be fair to earlier writers Viromandis is thought to be derived from the tribal name Viromanduens, but the relationship is more likely to be the other way round. The Viromanduens will have been the people of Viromandis, where the latter is a precise and correct topographical description of the location of Vermand, presumably the chief centre of the tribe.

1.3.3 Another possible example is Mondobriga, believed to have been at Alter do Chᾶo, located to the ENE of Lisbon. The town stands at the southern end of a hill stretched out in the NS direction, the highest point being at around 380 metres. Coming south the land drops down to an elongated terrace at around 330 metres, and continuing south the land then drops down to around 300 metres around the Castel de Alter do Chᾶo. Most of the modern town stands at this lower level, but the mond element of Mondobriga suggests that the original settlement was up on that terrace at around 330 metres. The brig element is then presumably just a transitional element in the hill-letter r, the element meaning ‘high hill steep’.

1.4 It thus seems sensible to conclude, even on the basis of this limited amount of evidence, that mand/mond is not derived from any hypothetical root mandu, taken to mean ‘small horse’ or ‘pony’, but is in fact a straightforward topographical compound in the hill-letters m and n, where the nd element means ‘hill summit’ or, more generally, ‘the top of raised ground’. The compound exists using other hill-letters in place of the m, for example using the hill-letter l in Landini (London or Streatley), Clindum (Clint) and Cambaglanda (Birdoswald), using the hill-letter r in Bograndium (Ardoch), and using the hill-letter s in Sandonio (Sandon on the river Trent).

2 Turning now to essedo, taken to mean ‘war-chariot’ or ‘cart’, again it will not normally be possible to prove or disprove that any place with a name including that element had any connection with war chariots or carts. But again, if it can be shown that place-names including that element refer to places having a particular topographical feature in common, then it will be sensible to conclude that the element actually refers to that topographical feature and has nothing to do with war chariots or carts.

2.1 The only other Romano-British name (i.e. other than Manduesedo) which appears relevant to this part of the discussion is Mugulesde, apparently the original spelling of Ravenna’s Ugueste at Stirling (the identification is explained in Chapter 16: Roman place-names in Scotland: the structure of the name is explained in Chapter 19: the rivers of Roman Britain and Chapter 17: the Roman invasion of Scotland). The esde ending in this name indicates that the place concerned was on top of the hill where the castle now stands. The meaning ‘war chariot’ seems inappropriate for Stirling – one could hardly run around the castle hill on a chariot, and much of the land around Stirling is thought to have been marshland in Roman days, so again chariots would not have been of much use there. And carts were presumably used for transporting supplies to the vast majority of forts, so it is not clear why this particular fort should have a name with an element actually meaning ‘cart’.

2.2 There are three places on the Continent which are thought to include the esedo/essedo element, namely Tarvessedum, generally thought to have been at Campodolcino, in a valley to the north of Lake Como, Metlosedo at Melun on the river Seine to the south of Paris, and Sidoloucom at Saulieu, to the north of Autun in Burgundy, France.

2.2.1 Campodolcino lies in the rather narrow valley of the river Liro, the valley being bounded on both sides by steep slopes rising to more than 1000 metres above the river. The valley widens out a bit at Campodolcino, but this wider area is stopped abruptly on its southern side by a hill jutting out from the main slope on the eastern side of the valley, this hill rising to only about 370 metres above the river. This does not appear to be suitable country for war-chariots, but, to be fair to earlier writers, the name Tarvessedum is generally thought to mean ‘bull-cart’, though it is not clear what that particular location should have to do with bulls or bull-carts. The first part of the name is not clear, but the essedum part appears more likely to be the old-style element sed meaning ‘hill summit’. Perhaps there had been an earlier fortified site on the top of that hill which juts out on the eastern side of the valley, the Romans then adopting this name and applying it to a post of some kind which they built down on the valley floor. A fortified site up on top of that hill would have given its occupants complete control over all movement along the valley. Moreover, on the assumption that the name Tarvessedum is indeed Celtic, and further on the assumption that there are no letters missing from the front of the name, then the name is likely to have been Daruesedum at an earlier date, where Dar is an inversion-type name-element meaning ‘summit of hill’ (entirely appropriate for the location) and qualified by the old-style element sed meaning ‘hill summit’. There may originally have been another consonant, possibly another hill-letter, between the u and the e.

2.2.2 Melun stands on the north side of the river Seine at the top of a north-stretching loop in the river, there being an island in the river at this point, so presumably this was an important crossing point on the Seine. The Roman name, as noted, was Metlosedum, though it is not clear why this particular location should be thought to have had any particular relationship to war-chariots or carts, the meaning generally given to esedo/essedo, though to be fair there are scholars who prefer yet another hypothetical root, sed, considered to mean ‘sit’. However, there is high ground coming in from all sides at Melun, this high ground coming close to the river to the east and north of the river at this point and being about 33-40 metres above the river. To the south, inside the loop of the river, the land rises gently towards the high ground. Metlosedum thus appears to be a straightforward topographical name in which the inversion-type element met is qualified by the older name of the place, i.e. by losed, where l is just the hill-letter l and sed means ‘hill-summit’. The Celtic settlement called Metlosedum will have been somewhere up on the high ground on the north side of the river Seine at Melun.

2.2.3 Sidoloucum at Saulieu stood on the eastern edge of an extensive area of high ground to the north of Autun in Burgundy, France. If the initial Sid has any connection with a hypothetical root essedo thought to mean ‘war-chariot’ or ‘cart’, it is not immediately apparent why war-chariots or carts should be of any particular relevance to this area. The immediate surroundings appear relatively flat at an altitude of around 580 metres, but the ground rises to the north, west and south. To the east the ground falls away into a river valley, the valley starting at a height of around 500 metres but dropping away to the east. The Sid element is thus more likely to be an old-style topographical element meaning ‘hill summit’. The hill in question, however, is perhaps not the slope just mentioned to the east of Saulieu – it is more likely to have been a slope in the immediate vicinity of the Gallo-Roman centre, and the author has seen a photograph showing some buildings in Saulieu standing at the top of a slope which drops down to a stretch of water. That stretch of water might possibly be a river, but it may instead be part of the water-filled ditch which is said to have extended round Sidoloucum. The remainder of the name is probably just the hill-letter l with a name-ending, though it may be that there had been another consonant between the o and the u at an earlier date.

2.3 It would thus appear that all five names, Manduesedo and Mugulesde in Britain, and Tarvessedum, Metlosedum and Sidoloucum on the Continent, were applied to places on the summit of a hill or, more generally, on the top of raised ground, and so it seems only logical to conclude that that is the information which is actually conveyed by the combination of the letters s and d, whatever the precise spelling of the element in the various names. That being so, we should dismiss the suggestion that that element is derived from a hypothetical root essedo assumed to mean ‘war chariot’ or ‘cart’.

The Bindo…./Vindo…. names

[Content transferred to Chapter 26: Appendix 2: Place-names with a Bindo or Vindo element]

1 The compound names of the Uxela, Iscalis, Loxa type form an interesting group. The Ravenna and Ptolemy names of this group are:

Uxela (169), Uxellum, Uxelis (13), Uxelludamo (152), Iscalis, Loxa (165), Uxella estuary, Traxula (236), Loxa, Iscaelis, Velox (271).

As always the numbering is that provided by Richmond and Crawford in Richmond and Crawford 1949.

2 The first six names are listed as place-names in Ravenna and Ptolemy, the other five as river-names. Uxela (169) and Uxellum are two slightly different forms of the same name, the name of the Roman fort at Chesterfield. The Iscaelis is of course the river called the Caelis in the Geography of Ptolemy.

3 The main difficulty with the above names is that the letter l can be a hill-letter or a river-letter, so that it is not always clear whether a name was originally a land-name (a place-name comprising hill-letters) or a river-name of the kind where the river-letter l is used as a prefix or a suffix to a land-name of the form ocs (an old-style element meaning ‘steep hill’) or isc (an inversion-type element meaning ‘hill steep’).

3.1 But in one case we can be certain. Uxella will have been a Celtic settlement adjacent a steep slope (most probably at the top of the slope) on or close to the river Parrett in Somerset (apparently Cannington Park hill-fort near Combwich), the name later being transferred to a Roman fort/settlement/harbour built nearby, and Parrett appears to be a Celtic river-name, probably Baret originally. The ux part of the name indicates that the the original settlement was adjacent a steep hill (x=cs), and the river-letters corresponding to the hill-letters s and l are b and t, both of which are present in Baret. The r in the middle of the river-name indicates that that area was once settled by people who used the hill-letter m. It thus seems quite clear that the l in Uxela (assuming there should be only one l) is the hill-letter l. Uxela is thus a straightforward old-style topographical place-name in the hill-letters s and l, the name having been transferred by the Romans to the river, hence Ptolemy’s Uxella estuary. But it was the Celtic name of the river, Baret, which survived in the modern Parrett. But note that if Ptolemy's Uxella is not a wrongly spellt form of Uxela, then the Celtic name may have been Ucselda or Ucselva (doubled consonants are rare in the earliest forms of Celtic place-names) where eld means 'hill-summit' and elv means 'hill-slope'. The Cannington Park hill-fort does embrace the summit of the hill, but it extends some considerable distance down the slope.

3.2 We can probably be equally sure in the case of Uxelludamo (Castlesteads). The dam part of the name is an inversion-type element meaning ‘summit of hill’, so clearly Uxel was the previous name of the hill, i.e. the l (assuming there should be only one l in the name) is the hill-letter l. Again, if the double l is not a mistake then the Celtic name may have been Ucseldudamo, where eld means 'hill-summit'.

3.3 Uxela (169)/Uxellum was the Roman fort at Chesterfield and so did stand adjacent a steep slope. Chesterfield stands on the river Rother and this river-name appears to be of Celtic origin. Consider, for example, Lemana in the south of England. The hill-letters l and m of this name correspond to the river-letters t and r, both of which are present in the name – East Rother - of the river which flowed past the fort until the military canal was constructed in the Napoleonic period. It thus seems quite safe to assume that the th in the Rother at Chesterfield is the river-letter t corresponding to the hill-letter l. In other words Uxela/Uxellum is an old-style compound in the hill-letters s and l.

3.4 Uxelis (13) appears to have been a Roman fort at Liskeard, though so far as the present writer is aware no trace of such a fort has ever been found. It would appear that Uxelis is yet another name which has been reversed at some stage, Lescis yielding the Lisk of modern Liskeard. However, whilst Uxelis is probably an old-style compound in the hill-letters s and l, we cannot be absolutely certain since the river flowing past Liskeard is the East Looe and so it is possible that the l in Uxelis is the river-letter l.

4 It is possible that Anglo-Saxon settlers took the l of Iscalis (the place-name Iscalis in Somerset transferred by the Romans to the river Axe) to be an element just meaning ‘river’, that they took isca to be the proper name of the river and that Isca later changed to Axe. It does appear, for example, that Anglo-Saxon settlers regarded the l of Alavna (the Avon at Stratford-on-Avon) as an element meaning ‘river’ and they adopted only what they saw as the proper name of the river, Avna, which later changed to Avon. It is therefore quite possible that the same happened with the Iscalis in Somerset, and that the Isca part of the name later changed to Axe. But the change may have happened during the Roman period. The river-name Isca (the Exe in Devon) appears to have been reversed at some stage, since if one reverses isca and adds a grammatical um to the end one has Acsium, which is of course Ravenna’s name Axium for the same river. It is thus possible that Iscalis was at some time reversed to give Lacsis, that later Anglo-Saxon settlers regarded the initial l as just meaning ‘river’ (exactly as in the case of Alavna) and that the proper name of the river then changed from acs to Axe. Something similar may have happened in the case of the river Traxula in Devon. This name simply means ‘river Axula’, but it may be that Anglo-Saxon settlers were told that the river was the Axula and that they regarded the l as an element just meaning ‘river’, the proper name of the river being, for them, the Axe. It is even possible that something similar happened in the case of Eburocaslum (Broomholm on the river Esk which flows into the Solway Firth), which appears to be a latinised version of a Celtic name such as Eburoucselum, where the ucselum element is a name of the kind discussed here. The fort was indeed built at the top of a high, steep slope, so the initial Ebur is probably just the old-style element br meaning ‘high hill’. The ucs element refers of course to the steep slope. It is of course also possible that the initial Eburo is just a variation of the Abra in Abravannus and the Br in Bribra, i.e. it is just a river-prefix attached to the place-name ucselum. But by whatever means it does appear that the ucselum element turned into the Esk of today. Again it is possible that this name was reversed and the initial l was taken by English-speaking settlers (even in that area) to be an element just meaning ‘river’, the proper name of the river being, for them, escu. English-speaking settlers are perhaps less likely to have had anything to do with the change from Iscaelis to Esk in the case of the river South Esk in eastern Scotland, but nonetheless it is likely that in this case, too, the modern river-name is derived from the Romano-British name.

5 That only leaves the Loxa names to be considered, namely Ravenna’s Loxa (165) and river Velox (271) and Ptolemy’s river Loxa. The name Velox seems to make sense only if we regard Lox as a compound in the hill-letters l and s, where the ocs element means, as usual, ‘steep hill’. The L of Lox must be the hill-letter l2, since the people who used this hill-letter appear always to have placed their river-letter t at the end of an existing river-name. It is this which accounts for the fact that the river-letter sequence in the river-name Brit (the Velox) is b, r, t, exactly the same as in the river-name Baret (the Parrett), even though this latter river-name is associated with the old-style place-name Uxella. What is a little surprising is that the river-name Velox starts with a V, this apparently being a modified river-letter b corresponding to the earlier hill-letter s in the name Lox. One might have expected T to be used since this corresponds to the later hill-letter l2 in the place-name. But it may be that there has been some confusion of v and t here, similar to that occurring in Ravenna's river-name Vividin (the Teviot in southern Scotland). The initial V of this river-name was surely originally a T, as in the modern river-name. Turning now to Ravenna’s Loxa (165) at Exley Head, Keighley, Yorkshire, this, too, looks like a straightforward compound in the hill-letters l2 and s (again x=cs). Note that Exley Head stands above the river Worth and the w and th of this river-name will originally have been b and t, giving a name somewhat like Bort, essentially the same name as the Brit at Lox and the Baret at Uxella. None of the place-names Uxella, Lox and Loxa includes the hill-letter m, though all three river-names Baret, Brit and Bort (Worth) include the corresponding river-letter r. This is odd, but nonetheless the order of the river-letters b, r, t in all three river-names is fully consistent with the normal chronological order of the hill-letters, namely n1, s, m, r, l1, n2, l2. Ptolemy’s river-name Loxa will have started out as the place-name Locsa of the Iron-Age settlement at Birnie, on the eastern side of the river Lossie at a point some six kilometres south of Elgin. The settlement stood immediately north of a hill with a very steep slope on its western side, adjacent the river, hence the ocs element, which means ‘steep hill’, the l in the name just being the hill-letter l1. The Romans then transferred the name of the settlement to a new fort which they built about a kilometre away, at Thomshill (NGR: NJ 211 574) and they transferred the name of their fort to the nearby river. Note that Loxa will have been the Roman name of the river. The Celtic name of the river most probably included the river-letters t and b corresponding to the hill-letters l and s in Locsa.

[The entry dated 22 August 2015 was last modified on 15 November 2022]